Designing a Tree Diff Algorithm Using Dynamic Programming and A*

During my internship at Jane Street1, one of my projects was a config editing tool that at first sounded straightforward but culminated in me designing a custom tree diffing algorithm using dynamic programming, relentlessly optimizing it and then transforming it into an A* accelerated path finding algorithm. This post is the story of the design and optimization of the algorithm, of interest to anyone who needs an algorithm for diffing trees, or who just wants an in-depth example of the process of solving a real-world problem with a custom non-trivial dynamic programming algorithm, and some tips on optimizing one while maintaining understandability, or anyone who just wants to read a cool programming story and maybe learn something.

Table of Contents

- Background: Description of the problem I was solving.

- The Heuristic Approach: My initial attempt at a simple algorithm, and why it was insufficient.

- A Tree Diff Optimizer: Rethinking the problem as finding the optimal resulting tree diff.

- Dynamic Programming: Background on using the correspondence between memoizing recursion and path finding on a grid to find solutions to problems like Levenshtein distance.

- The Algorithm: Extending Levenshtein distance with two grids and recursion.

- Profiling and Optimizing: Relentless profiling and optimizations to reduce run time.

- Path Finding: Using A* to make the run time proportional to the difference rather than tree size.

- Example Implementation: Analysis of the effectiveness and costs of A* on Levenshtein distance, sequence alignment and diffing problems, with open source example code.

Background

Jane Street has a lot of config files for their trade handling systems which use S-expressions (basically a tree with strings as leaves). They often want to make changes that will only apply on certain days, for example days when markets will act differently than normal like elections and option expiry dates. To do this their config processor knows a special construct that is like a switch statement for dates, it looks something like this:

(thing-processor-config

(:date-switch

(case 2017-04-07

(speed 5)

(power 7))

(else

(speed 3)

(power 9))))The semantics are that any :date-switch block has its branches checked against the current date and the children of the correct branch are used in place of the :date-switch in the config structure. Note that each branch can contain multiple sub-trees.

Now, just that small example took a while for me to type and get the indentation correct. People at Jane Street are frequently making edits where they just want to quickly change some numbers but have to make sure they get the syntax and indentation right and have everything still look nice. This is begging for automation!

So they asked me to write a tool that would allow people to just edit the file and run a command, and it would automatically scope their changes to the current day, or a date they specify, by detecting the differences between the current contents on disk and the committed contents in version control.

When I first heard the problem, it sounded pretty easy and I thought I’d be done within a few days, but I discovered a number of catches after starting and it ended up taking 5 weeks. This sounds like we maybe should have abandoned it when we discovered how complex it was, but given how much time expensive people were spending doing these edits, sometimes under time pressure when every extra minute had a high cost, it was worth it to get it right.

The first thing I discovered is that they had a library for parsing and serializing s-expressions while preserving indentation and comments, but it didn’t cleanly handle making structural modifications to the parse tree. Before even starting the rest of the project I had to write a library that provided a better data model for doing this and having the result be nicely indented.

Next, the real syntax for these date switch blocks is more complicated than my description and has a static constraint where the branches must cover every date in the current context and no more, including when nested inside other switches. I also didn’t want edits to :date-switch blocks to themselves be scoped to a date, since that would create invalid syntax. This required I parse my earlier style-preserving representation into one that computed date context and represented :date-switch blocks specially in an Abstract Syntax Tree (AST) as well as transform back from my representation to the one I could output.

Now finally I was ready to start on the actual algorithm. The basic task my script had to do was take two trees and wrap differing sub-trees in a :date-switch block with the old contents in one branch and the new contents in the other branch. The thing is, there are many ways to do this. The switch can be placed at many different levels and there may be multiple edits and it’s not specified how to group them. Technically it could just add a :date-switch at the top level with the old file in one branch and the new file in another, but that wouldn’t be very satisfying, just like how technically the diff command could just output the entire old file prefixed with - and then the new file prefixed with +, but then nobody would use it. I needed an algorithm that gave reasonable-looking and compact changes for real-world edits. It shouldn’t double the file size in an enormous :date-switch when only a single number changed.

The Heuristic Approach

If you just want to read about the optimal algorithm and not why one was necessary you can skip this section.

First, I came up with a simple algorithm that I thought would work in almost all real-world cases. I simply recursively walked down the tree until I got to either a leaf that was different or a node that had a different number of children, and then it would put a :date-switch at that level.

This didn’t produce the most satisfying results, it was okay for changes to leaves, but as soon as you added or removed a child from a list, it would duplicate most of the list when it could have taken advantage of the ability to have a different number of children in each branch.

It produced this:

(:date-switch

(case 2017-04-07

(foo

qux

; ... 1000 more lines ...

baz))

(else

(foo

; ... 1000 more lines ...

baz)))When we really would have preferred:

(foo

(:date-switch

(case 2017-04-07 qux)

(else))

; ... 1000 more lines ...

baz)Luckily, this was easy enough to solve since Jane Street already had an OCaml library implementing the Patience Diff algorithm for arbitrary lists of comparable OCaml types. When I had two lists of differing length, I simply applied the Patience Diff algorithm and placed :date-switch blocks based on the diff.

This algorithm worked okay for cases of a single edit, but we wanted the tool to work with multiple edits, and for those it still often produced terrible results.

For example, because it stopped recursing and applied a diff as soon as it reached a list of changing length, it would do this:

(this

(:date-switch

(case 2017-04-07

(bar

; ... 1000 more lines ...

baz))

(else

(foo

; ... 1000 more lines ...

baz)))

tests

(:date-switch

(case 2017-04-07 adding to a list and modifying a sub-tree)

(else)))It duplicates the long sub-tree instead of placing the :date-switch lower down in it, just because we made another edit at a higher level of the tree.

There were a number of other cases where it didn’t produce output as nice as a human would, but earlier on my mentor and I had sighed and accepted it. This though was the last straw, we needed a new approach…

A Tree Diff Optimizer

At this point I was fed up with constantly discovering failure modes of algorithms I thought should work on real-world cases, so I decided to design an algorithm that found the optimal solution.

I started by searching the Internet for tree diff algorithms, but every algorithm I found was either a different kind of diff than what I needed, or was complex enough that I wasn’t willing to spend the time understanding it (probably only to later find out it computed a different kind of diff than I needed).

Specifically, what I needed was mostly like a tree diff but I wasn’t optimizing for the same thing as other algorithms, what I wanted to optimize for was resulting file size, including indentation. This I thought represented what I wanted fairly well, and captured why previous results which duplicated large parts of the file were bad. As well as the character cost of the branches, each additional :date-switch block added more characters. Additionally, each switch construct could also contain multiple sub-trees in each branch, which I needed to model to account for overhead correctly.

Consider the case of (a b c) becoming (A b C). A human would write:

(:date-switch

(case 2017-04-07 (A b C))

(else (a b c)))Despite the fact that the b is duplicated, this is the smallest number of characters. However if we had something longer we’d want something different, so the optimal result even depends on the length of leaf nodes:

((:date-switch (case 2017-04-07 A) (else a))

this_is_a_super_long_identifier_we_do_not_want_duplicated_because_it_is_looong

(:date-switch (case 2017-04-07 C) (else c)))A very common real-world example of why it is important for it to be able to batch together differences is when changing multiple values of a data structure. The config files often have lots of key-value pairs and edits often touch many nearby values:

(thing-processor-config

(:date-switch

(case 2017-04-07

(speed 5)

(size 80)

(power 9001))

(else

(speed 3)

(size 80)

(power 7))))Even though size didn’t change, we duplicate it because it’s cleaner than having two :date-switch blocks.

Dynamic Programming

After 2+ days of research, discussing ideas with my mentor, and sitting down in a chair staring out at the nice view of London while thinking and sketching out cases of the algorithm in a notebook, I had something. It was a recursive dynamic programming algorithm that checked every possible way of placing the :by-date blocks and chose the best, but used memoization (that’s the dynamic programming part) so that it re-used sub-problems and had polynomial instead of exponential complexity.

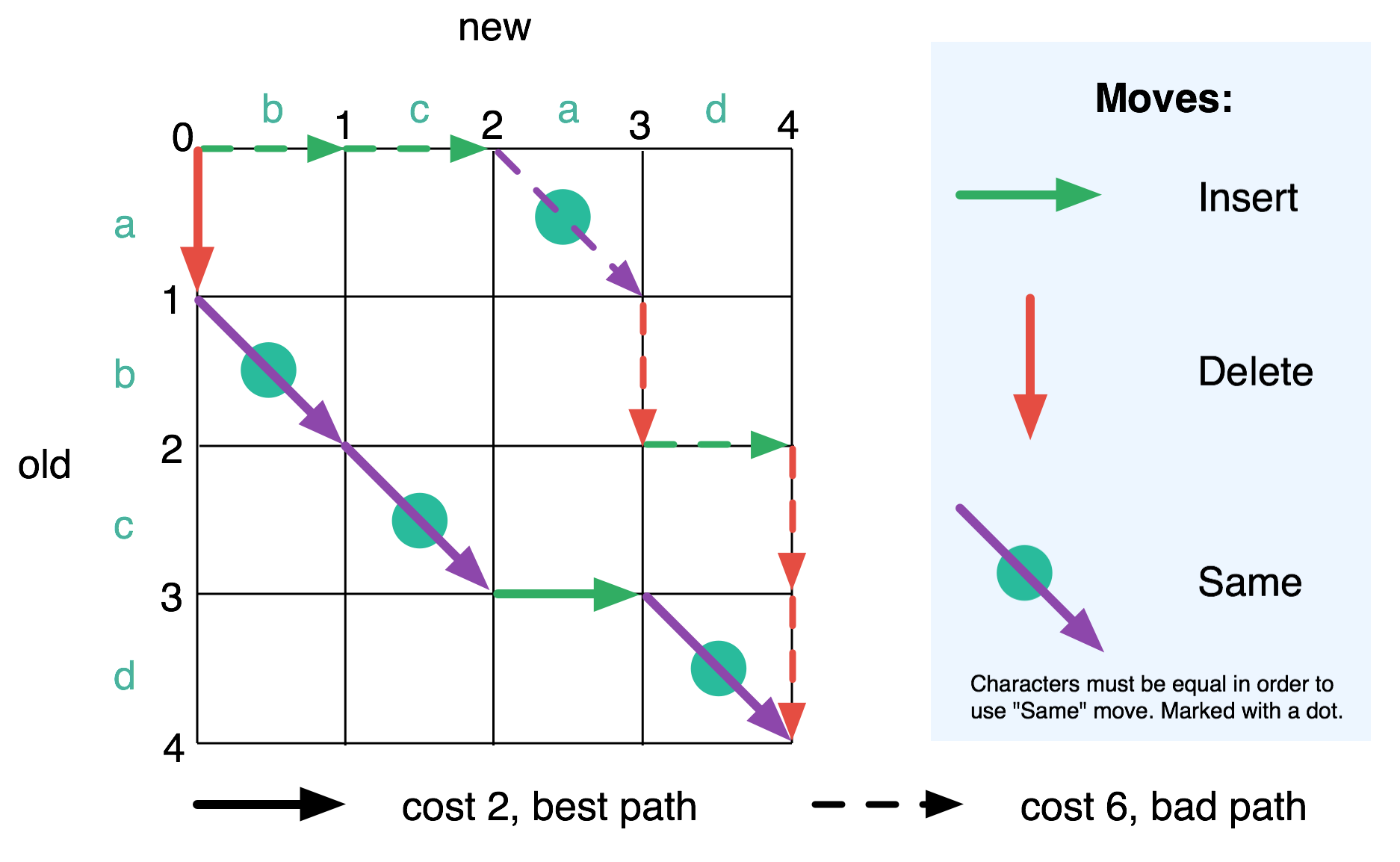

The core of the tree diffing problem is similar to the Levenshtein Distance problem, you have two lists that have some number of insertions and deletions between them, and you want to find the best way to match them up. You can do this with a number of different cases based on the first elements of the lists with different costs, calculating those costs involves some constant plus recursively computing the cost for the rest of the lists. Then you compute the cost for each possible decision and take the minimum one.

For example if you have a function best_cost(old,new) to solve the Levenshtein distance problem, there’s three cases for the start of the lists: insert, delete and same. The simplest case is if the first two elements are the same, and characters that are the same cost 0, then the cost is just best_cost(old[1..], new[1..]). If a delete costs 1, then if the start of the list is a delete that means the character is in old but not new so the total cost is 1 + best_cost(old[1..], new). Insert is similar but the opposite direction. This recursion terminates with the base case of best_cost([],[]) = 0. The problem is that this leads to an exponential number of recursive calls.

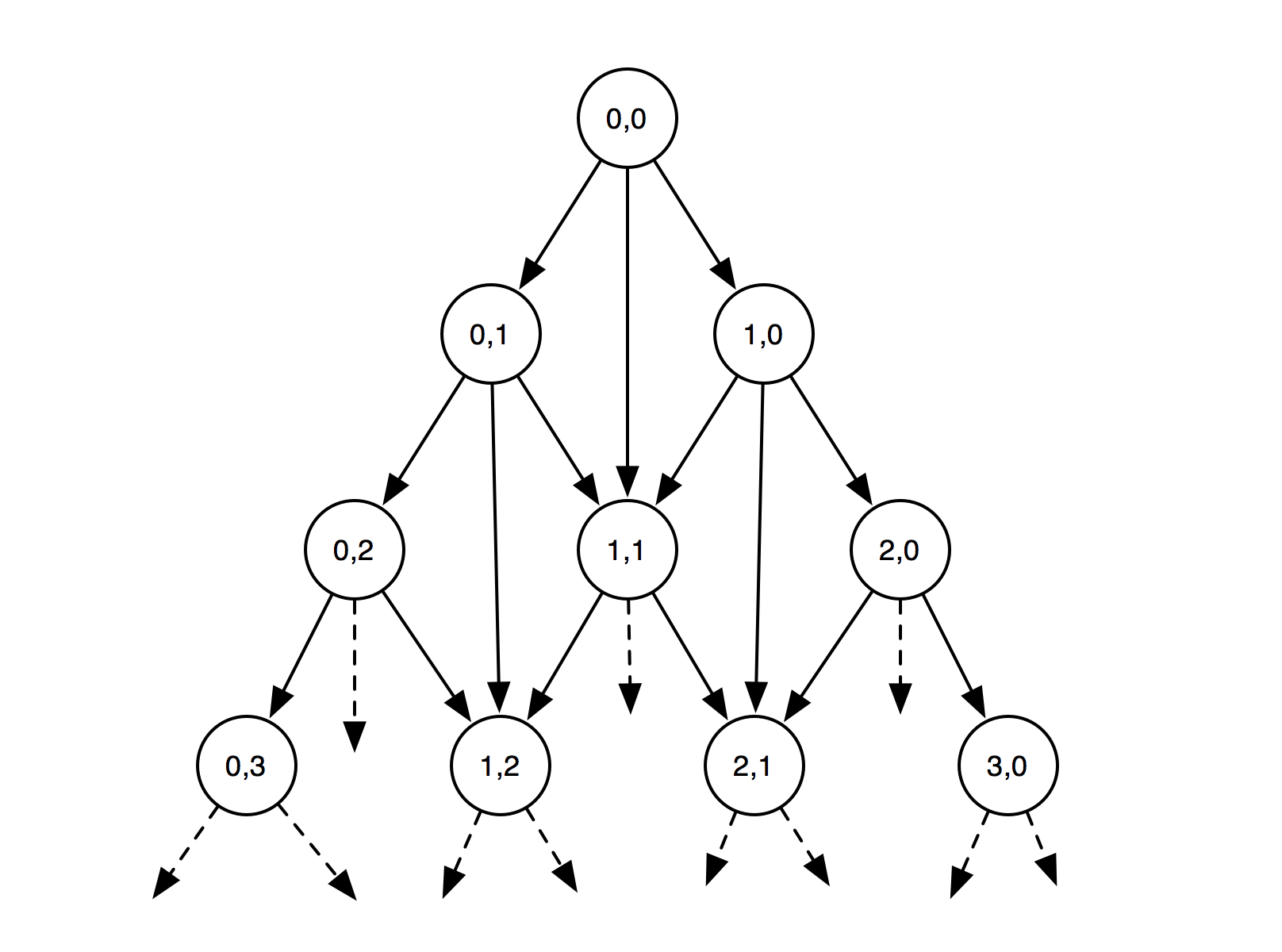

But we can fix this by noticing that a lot of things are being computed redundantly and sharing the results by “memoizing” the function so that it stores the results for arguments it has been called with before. As seen in the diagram below, where the numbers on the nodes represent calls to best_cost(old[i..], new[j..]) as i,j:

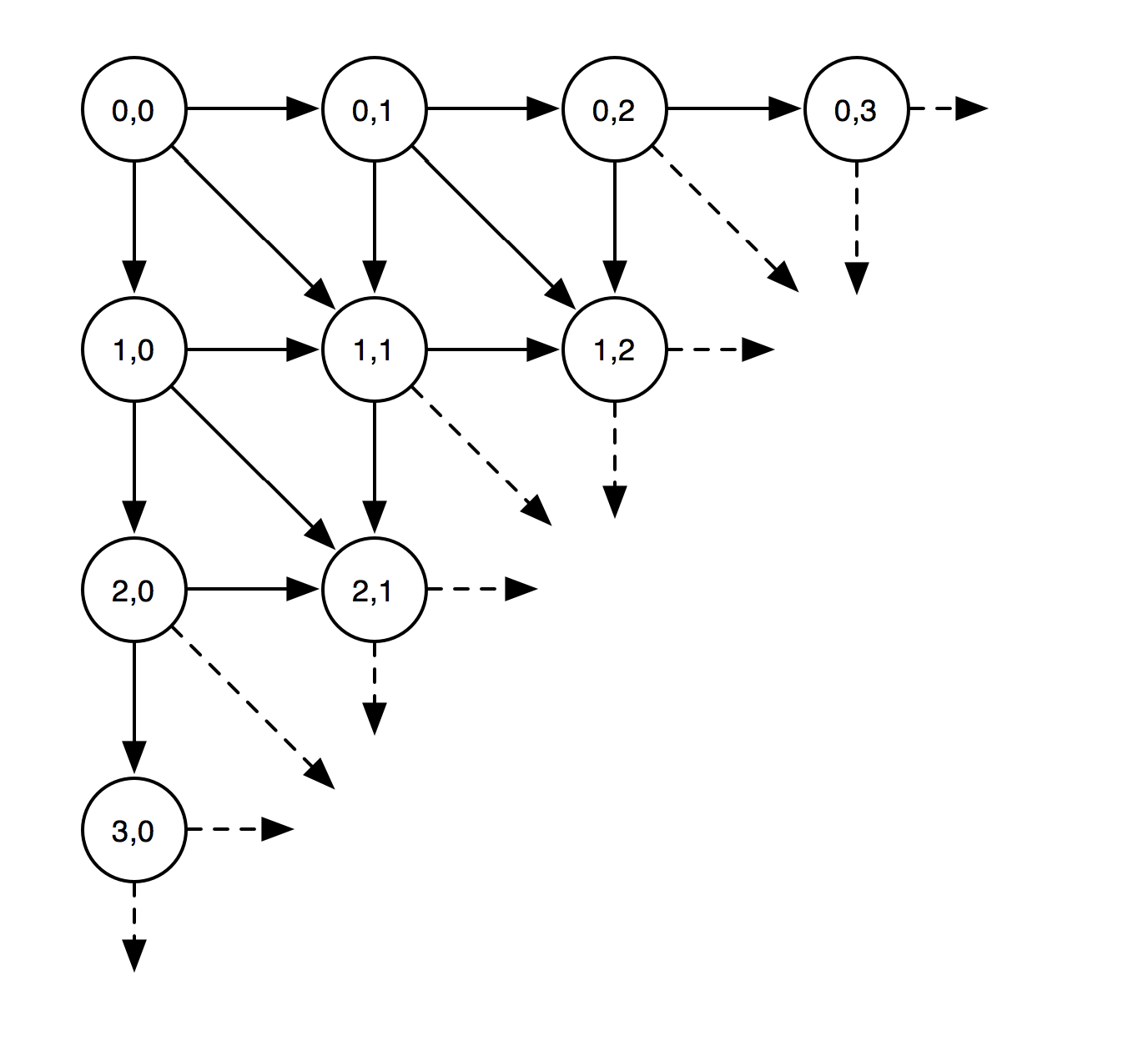

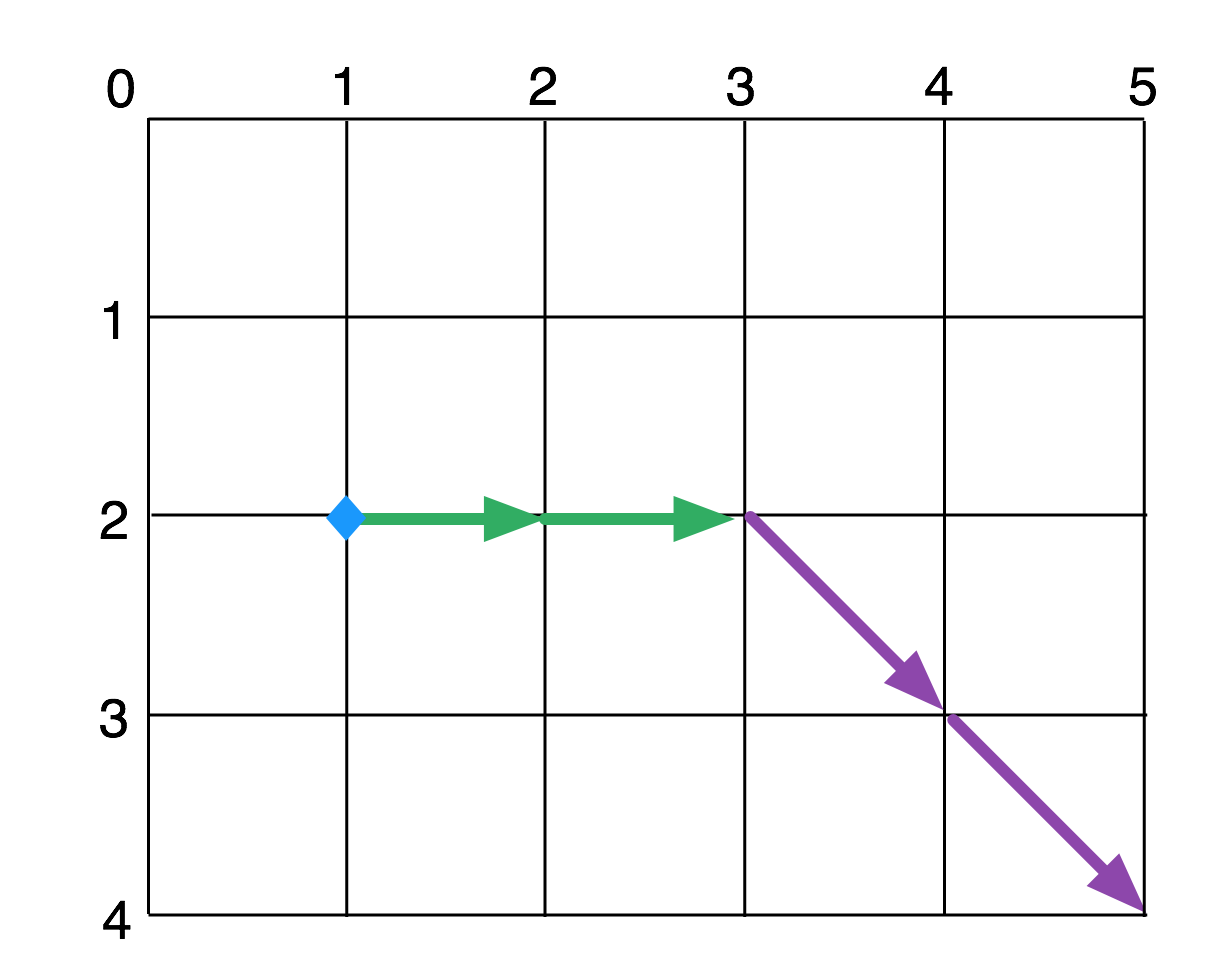

But in some cases it can be difficult to think about the problem as a recursive memoized decision tree. Luckily there’s a different way of thinking about it that lends itself very well to sketching out algorithms in a notebook or on a whiteboard. We can rotate the tree 45 degrees and notice that we can think about it as a grid:

This is useful for memoization since it means we can store our results in an efficient-to-access 2D array, but also because we can now think of our problem as finding a path from the top left of a grid to the bottom right using a certain set of moves. Whenever our decisions are constrained we can annotate the grid where the input lists have a property, like two items being the same. In the example below, we have a diagram of trying to find the Levenshtein distance from “abcd” to “bcad”, with the best path bolded, and an alternative more costly path our algorithm might explore shown dashed.

We can find the best path by testing all the paths and returning the best one. There are exponentially many paths, but we can notice that the best path from a point in the middle of the grid to the bottom right is always the same no matter what moves might have gotten us to that point.

One way to exploit this is to recursively search all paths from the top left, memoizing the best path at each point so we don’t compute it again. This corresponds to the memoizing of recursive functions mentioned earlier and is called the “top-down approach” to dynamic programming.

There’s also the “bottom up” approach where you start from the bottom right and fill in each intersection with the best path based on previously computed results or base cases by using an order where everything you need is always available. In this case it would be right to left, top to bottom, like reading a book from end to start.

Now we know that if we can restate our tree diffing problem as a problem of path-finding on a graph, we can turn that into an implementation using dynamic programming.

The Algorithm

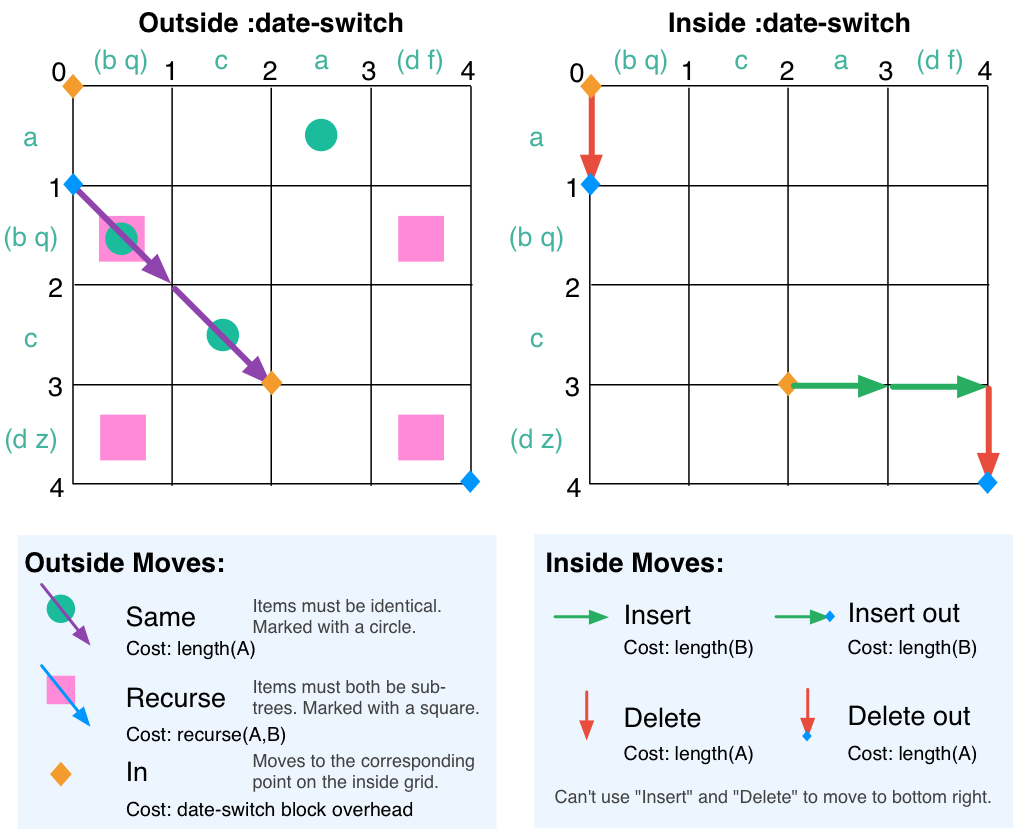

The key differences between my problem and Levenshtein distances were the fact that it was a tree and not a list, and the fact that consecutive sequences of inserts/deletes were cheaper than separate ones (because consecutive edits could be combined in one :date-switch block). My cost function is also different in that I’m measuring the size of the resulting tree including :date-switch blocks, so my moves will need costs based on that.

I can extend the list algorithm to trees by adding a move I’ll call “recurse” that goes down and right and can be done on any square where both items are sub-trees (not leaves). The cost of the move is the cost of the resulting diff from running the entire tree-diff algorithm recursively on those two sub-trees. I don’t bother recursing if the two sub-trees are the same, since the “same” move has identical cost in that case, and is faster to compute.

We can handle the cheaper consecutive inserts and deletes by modeling entering and leaving a :date-switch block as moves. However now we have different move sets based on if we are in or out of a :date-switch block and different costs to get to the end from a given point. We can rectify this by splitting our problem into path-finding over two grids of the same size. One is our “outside” grid, where we can do the “same”, “recurse” and now also a “in” move which moves us to the same position on the other grid.

On the “inside” grid we can do “insert”, “delete” and “out” moves. But that won’t quite work because if “in” and “out” both don’t make forward progress, the graph has a cycle and our search algorithm will endlessly recurse over paths going “in” and “out” at the same point. We can solve this by splitting “out” into “insert out” and “delete out”. The first two are the same as insert and delete except they also move to the “outside” grid, we also have to make sure that we don’t use the “insert” and “delete” moves to go to the bottom right of the “inside” grid, because then we’d be stuck.

This gives us a set of moves that always make forward progress and share as much as possible, with this we can find the best path and that gives us an optimal diff. See the diagram below which also includes the cost of each move and an example path, although not necessarily the optimal one:

Even this model is simplified, because in reality I had to handle input lists that both might have :date-switch blocks already in them, so there were a bunch more cases and contingencies for handling existing :date-switch blocks properly. But those aren’t very interesting and the core of the algorithm is the same.

So I implemented this algorithm on top of the AST manipulation framework I’d built by translating it to a memoized recursive algorithm operating on linked lists. Since the outer algorithm also involved recursion, this meant I had two kinds of recursion, which I structured using OCaml’s ability to define functions inside of other functions. I had an outer scope_diffs function that took two lists of s-expressions and produced a list of s-expressions with differences scoped by :date-switch blocks. Inside it, I allocated two tables to memoize the results in, and defined scope_suffix_diffs_inside and scope_suffix_diffs_outside functions that took indices of the start of the suffixes and mutually recursed and memoized into the tables based on the moves above.

Unlike the Levenshtein difference algorithm I wanted more than just the cost, so I stored the actual scoped s-expressions up to each point in the table directly, because I was using immutable linked lists in OCaml this was memory-efficient since each entry would share structure with the entries it was built from. This way I avoided the back-tracing path reconstruction step that is frequently used with dynamic programming. In order to make the lists share structure I did have to add to the front instead of the back, but I just reversed the best resulting list before I returned it.

Once I finished programming it and got it to compile, I think I only had to fix one place where I’d copy-pasted a +1 where I shouldn’t have and then it worked beautifully. Finally, unlike all my heuristic attempts, I couldn’t find a case where this produced a result significantly worse than what a human would do.

Side note: I used to expect lots of debugging time whenever I finished a bunch of complex algorithmic code, but to my surprise I’ve found that’s rarely the case when using languages with good type systems. The compiler catches almost all small implementation errors, and since I’ve usually spent a long time thinking about all the edge cases carefully while designing the algorithm, there’s usually no serious bugs left by the time it compiles. My tests usually fail a few times, but that’s normally because I wrote the tests wrong.

Unfortunately, while my new algorithm worked quite well for small files, it was very slow on large files. My mentor timed it on a few example files and fit a polynomial and discovered that it was empirically O(n^3) (or it might have been O(n^4) I forget) in the file size. This was unfortunate since some of the files were tens of thousands of lines long. I had to make it faster, luckily while I’d been thinking about and implementing the algorithm I’d accumulated quite a list of optimization ideas to try. But first, I decided to profile to see what the biggest costs were.

Profiling and Optimizing

Incremental cost computation

The first order of business was to discover why the empirical complexity was higher than we thought it should be. My mentor and I tried to come up with a proper analysis of what it should be, but given all the cases and the nested nature of trees there were just too many parameters and we couldn’t come up with anything precise. But, as far as we could tell the complexity of the underlying algorithm should have been about O(n^2*log(n)) in the length of real files.

I could have looked over the implementation carefully to find all the extra unnecessary work, but an easier method was just to use the Linux perf tool to profile it. I knew the work that caused it to be O(n^3) wasn’t at the outer levels of the algorithm, or I would have noticed easily, so it had to be an operation within that would show up in the profiles.

Sure enough, most of the program’s time was spent in the code that computed the length/cost of an s-expression. I had a function that walked a tree and computed its total length, and in the part of the algorithm where I had to choose the lowest-cost move I computed the cost of the entire path from that point, which added an extra O(n) inside the O(n^2) algorithm yielding O(n^3).

In order to fix this, I made sure every cost computation was constant time, which meant I had to construct the cost of a path incrementally as it was constructed, and also not repeatedly walk trees to determine their cost.

I solved this in three steps:

- Create a “costed list” type which was a linked list except each item included the cost of the suffix from that point. This had a constant-time prepend operation that just added the cost of the item being prepended to the cost field of the rest of the list.

- Modify the Abstract Syntax Tree (AST) data structure to include a cost field on every node, and to use a costed list for children. I also made all the AST builder functions compute the cost of their components by just adding the cost of their overhead with the costs of their child nodes or costed lists. Now both getting the cost of an AST subtree and constructing a node were constant time.

- When building the path/diff/result of my algorithm I used a costed list and constructed new

:date-switchnodes using the constant-time builder API.

After I did this, our measurements of growth were consistent with the O(n^2*log(n)) we were expecting.

Skipping identical prefixes and suffixes

This was an easy but high-impact optimization I had written down earlier. By the properties of the cost of each move, if a prefix and/or suffix of the two lists was identical, the “same” move would always be the best for those parts of the path. This meant that I could find the longest prefix and suffix of the two lists that was the same and only run the dynamic programming algorithm on the middle part that wasn’t. This made the common case of edits being concentrated at a single point in the file very fast because now the running time was more like O(d^2*log(d)+n) with nbeing file size (large) and d being the size of the edited region (small).

Now almost all common uses of the tool would return instantly except edits in multiple places spread out through a large file. It was now a pretty useful tool, but users having to know which cases to avoid to make the tool not take forever wasn’t great. It would sometimes be used in high-pressure situations and often people did want to make edits in different places, manually batching the edits up and running the tool multiple times wasn’t ideal.

There was also only one or two weeks left in my internship, not much time to do another project, and I think my mentor was having fun challenging me to make the tool perfect and brainstorming how to do so with me. I was also enjoying the process, so the optimization would continue until performance improved!

Tree creation optimization

Profiling indicated a lot of time was spent creating :date-switch AST nodes.

First I wrote a fast-path method of creating and computing cost for :date-switch blocks the algorithm creates since they use a simpler format and a known indentation style than the more general AST construction builder uses.

Additionally, when exploring paths in the “inside :date-switch” table, I used to create a :date-switch node whenever I needed to know the cost so far to decide between moves. Instead, I switched to just adding the costs of the insert and delete branches (which were costed lists), to a known overhead of the :date-switch block. I only created the full node upon exiting to the “outside :date-switch” table.

But my mentor realized this could extend even further: The search for the best path only ever needs to know the cost of a resulting path/tree, we only need the full tree for the best path at the end of the search. So I added a “lazy :date-switch” AST node that has a stored cost computed by fast addition of the cost of the components plus a known overhead, but doesn’t actually create the node immediately and just stores an OCaml lazy thunk that creates it if we try to serialize the result.

More?

My tool was now instant in most common cases and difficult cases were over 100x faster. But, on the very largest 10,000+ line config files it would still take up to 5 minutes in the worst case if you made edits in multiple places. There were no longer any obvious hot spots in the profiles, I needed algorithmic improvements that let me search less possible paths.

I looked at my list of optimization ideas and there was only one left, which I had written down early on in the process when thinking about the correspondence between dynamic programming and path finding on a grid. It was just a few characters in a Markdown note that I had saved for if I was feeling ambitious and really needed it: “A*”.

Path Finding

Back when I was designing the algorithm by thinking about it as a path finding problem, I thought “hey wait, if this is a path finding problem, why not use an actual path finding algorithm?” The first thing I realized is that the memoized recursion approach I was planning on taking was just a depth first search, which can be a path finding algorithm, but not a particularly good one.

Could I use a better path finding algorithm? Breadth first search wouldn’t help much since the goal was near the maximum distance in bounds. However, A*, perhaps the most famous path finding algorithm, seemed like it might help, if only I could come up with a good heuristic. So I wrote it down without thinking too much and came back to it later after I had done all my other optimizations.

The last time I learned A* was when I read Algorithms in a Nutshell (good book) years ago and all I remembered was that it needed a priority queue and a good heuristic. I had a Heap for the priority queue, but I didn’t remember how to actually implement it or what a good heuristic was, so to Wikipedia I went!.

I learned that I needed a heuristic that never overestimated the remaining cost, and that ideally never decreased more than the cost of any move taken. One thing that satisfies those properties is the maximum of the costs of the two list suffixes from a location. This corresponds to the notion that a scoped config file that includes the contents of both config files can’t be smaller than either of the input files. This heuristic was easy to compute using the costed list representation I already had, which already has the cost of each suffix of the input lists.

With a heuristic and an understanding of A* in hand, I refactored the implementation of my algorithm to work by putting successor states in a priority queue based on their cost plus the heuristic remaining cost. This required changing each instance of recursion on my table into the creation of a State structure that encompassed if I was inside or outside of a :date-switch, and the current position.

I also had to make two changes to my data structures. First, since I was no longer using recursion to destructure my linked lists but was now indexing them, which is O(n), I created arrays of the tails of my input costed lists so that random access was fast. Next, my solution still used O(n^2) memory in all cases due to the 2D array memoization table, so I switched that to a hash table from position tuples.

Profiling now showed a lot of time was then spent in hash table lookups, so I experimented with dynamically using a 2D array for small input lists (like were often found on the lower levels of the tree) and a hash table for larger input lists, but further profiling showed it didn’t increase performance much, probably because most of the lookups were in the larger lists, so I stuck with plain hash tables.

After a little debugging of off-by-one errors, I ran the program on my largest test case and it finished instantly. It was so fast I was suspicious it was broken and just skipping all the work, but sure enough it worked perfectly in every case I threw at it. The cost was something like O(n * log(n) * e^2) where n is the file size and e is the number of edits. Me and my mentor managed to think of some edge case trees where it might revert to O(n^2) behavior, and it still only scaled to config files of tens of thousands of lines rather than hundreds of thousands, but it was nearly instant for all cases that might actually occur, so it was good enough™.

I spent the remaining 3 days of my internship polishing up the user interface of the tool, cleaning up the code and writing lots of doc comments explaining my algorithm. I also gave a presentation to a bunch of the other engineers telling a shorter version of the story I’ve written here. That marked the end of my internship with Jane Street and one of the most interesting algorithmic problems I’ve ever worked on, despite it being part of a tool for editing configuration files.

Example Implementation

I was curious about how the approach of turning a dynamic programming problem into an A* path finding problem scaled and how applicable it was to other problems. So, I developed an example implementation of this approach in Rust for the sequence alignment problem, which Levenshtein distance is a specific instance of. It’s structured for simplicity and I haven’t optimized it at all, but it’s good enough to demonstrate the asymptotic improvements.

The core code of the algorithm is fairly simple and is a good demonstration of the logic required to turn a dynamic programming algorithm into an A* path finding instance. It allows you to tune the weights of insertions/deletions, mismatches and matches of characters in the two strings, so that you can change it to be Levenshtein distance or some other instance of sequence alignment.

The heuristic it uses is based on splitting the remaining distance to the bottom right corner into two components: the minimum number of insertion/deletion moves necessary to get on the diagonal from the goal, and the minimum number of match moves necessary to get from that place on the diagonal to the goal. This represents the minimum possible cost required to reach the goal from any position without knowing what the actual best path is.

fn diag(pos: &Pos) -> i32 {

(pos.1 as i32) - (pos.0 as i32)

}

fn heuristic(pos: &Pos, goal: &Pos) -> Score {

// find the distance to the diagonal the goal is on

let goal_diag = diag(goal);

let our_diag = diag(pos);

let indel_dist = (our_diag - goal_diag).abs();

// find the distance left after moving to the diagonal

let total_dist = max(goal.0 - pos.0, goal.1 - pos.1) as i32;

let match_dist = total_dist - indel_dist;

return (indel_dist * INDEL) + (match_dist * MATCH);

}

Discoveries

Here’s some things I learned by fiddling with the program and timing it:

- As expected, the algorithm only tends to explore states along the diagonal of the grid, with the width of the area explored proportional to the edit distance. This suggests the running time is something like

O((a+b) * e^2)whereaandbare the input lengths andeis the edit distance. - Running it on a 10,000 base pair gene sequence with an edit distance of 107 takes 0.26 seconds.

- Running it on a 10 megabyte random text file with 1 edit near the beginning and 2 near the end takes 20 seconds and evaluates 40 million states. This is a case where with the

O(n^2)algorithm just allocating and zeroing4*10^14bytes of memory for a table with the naive algorithm would take forever. Demonstrating that this optimization does in fact provide an asymptotic speed up. - It’s still way slower than specialized sequence alignment implementations like Edlib, probably asymptotically so. These implementations use all sorts of fancy tricks including fancy algorithmic tricks, SIMD and bit vectors to eke out maximum performance for bioinformatics applications. My implementation is at least way way simpler.

- Plain Dijkstra’s algorithm (A* with a heuristic always returning 0) actually performs almost as well for Levenshtein distance because only edits have cost so it explores along the diagonal towards the goal along the path with less edits just because those have lower cost. However, if the problem has a cost for matching portions as well (like my original tree diffing problem) Dijkstra’s algorithm will explore in a blob expanding from the top left and be almost as slow as the naive algorithm.

- With a heuristic, Levenshtein-distance like instances where only edits have cost take about the same time to run as instances like my tree-diffing problem where matching segments also have cost.

Conclusion

A* is an interesting technique that’s an easy way to accelerate a class of dynamic programming problems. It definitely works on any vaguely diff or edit-distance like problem, but it might extend to even more. If you want absolute peak performance on a simple algorithm there’s probably better techniques to use, I’d start by looking at what bioinformatics people do, but if you just want something easy and flexible this seems like a good technique, and it’s not one I’ve seen done before, and Google doesn’t turn up any results. It might even be novel, or it might just be that A* is a hard term to Google for, I’m interested to hear from anybody who’s seen something like this before.

-

A great place to work, highly recommend. I did get Jane Street’s permission before divulging the algorithm I wrote for them in this post. ↩