Shenanigans With Hash Tables

One reason to know how your data structures work is so that when your problem has unusual constraints you can tweak how they work to fit the problem better or work faster. In this article I’ll talk about four different fun tweaks to the concept of a hash table that I made in the process of using hash tables to implement interface method lookup vtables in my compilers class Java-subset compiler. The fact that I knew the contents and lookups of all the tables at compile time allowed me to heavily optimize the way the hash table worked at run time until the common case was just indexing an array at a constant offset! Even outside the context of compilers, I think this is an interesting source of inspiration for the ways you can tweak data structures for your purpose.

Background on vtables and interfaces

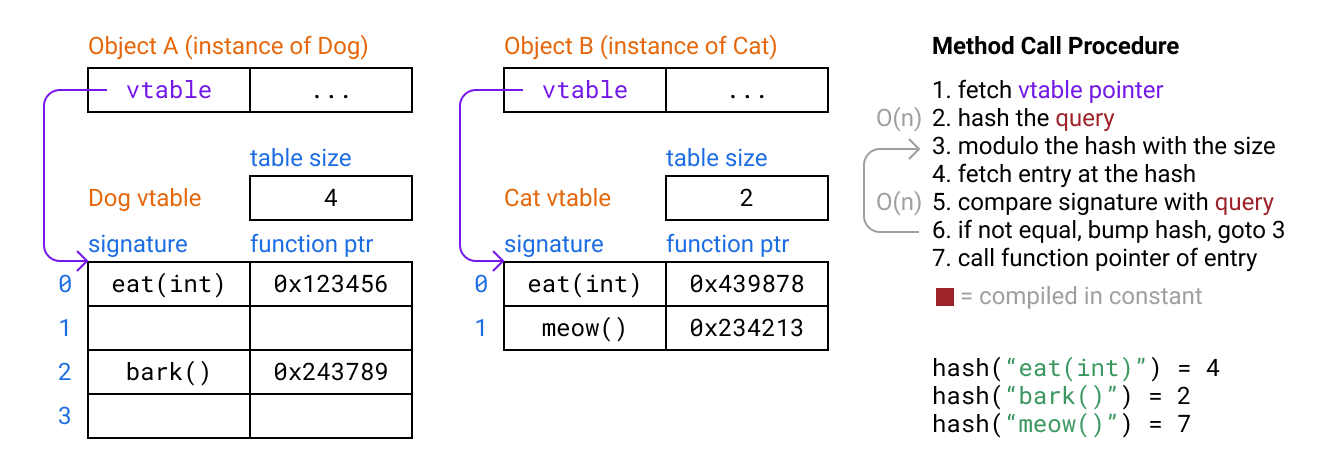

For object-oriented languages, compilers usually use “vtables” to implement method dispatch. This is when every object has a pointer to an array of function pointers corresponding to the different methods on that object. Each method has a fixed slot, with methods in base classes coming before inherited ones so that an object can be treated as its base class with the same offsets.

The problem is that implementing interfaces is harder since the vtable prefix trick doesn’t work. Java HotSpot implements interface method calls doing a linear search over a list of “itables” for each interface an object implements, then using inline caching and fancy JIT specialization to speed that up in the common case.

The simpler alternative is to make a giant table of every method signature present in the program (for Java that’s name and parameter types like addNums(int,int)), each class will have an instance of this table with the slots for methods it implements filled in (including ones inherited from superclasses), and most slots empty. Then for interface dispatch you can just use a fixed offset for the interface method signature: easy and fast. The problem is the size of each table scales with the size of the program, and so does the number of tables, leading to O(n^2) scaling, making this technique non-viable for large programs.

Hash vtables

Instead of using a giant fixed table, we can use a hash table from method signature to method pointer. Since every table doesn’t need to be large enough to fit all method signatures in the entire program, this solves the scaling problem. For simplicity we’ll use linear probing to handle the case when our hash tries to put two methods in the same slot: we put the colliding method in the next available slot.

However this is now much slower than simple tables. A simple hash table lookup with linear probing includes two operations that need to loop over the bytes in the signature as well as a probing loop:

struct TableEntry {

char *signature; // assume signatures are strings for simplicity

void *fnAddr;

}

void *lookup(TableEntry *table, size_t tableSize, char *query) {

uint32_t queryHash = hash(query); // <- O(n) in signature length

// look in the next slot if a collision bumped our target from its place

for(;;queryHash++) {

queryHash %= tableSize;

TableEntry entry = table[queryHash];

if(strcmp(query, entry.signature) == 0) { // <- O(n) in signature length

return entry.fnAddr;

}

}

}

Why use queryHash %= tableSize instead of just indexing with queryHash % tableSize? I did that in the initial draft of this post, but then I realized it breaks when the initial hash is close to the maximum integer and probing causes queryHash to overflow to zero. That would have been a very evil bug since it would silently give the wrong result but only exceedingly rarely.

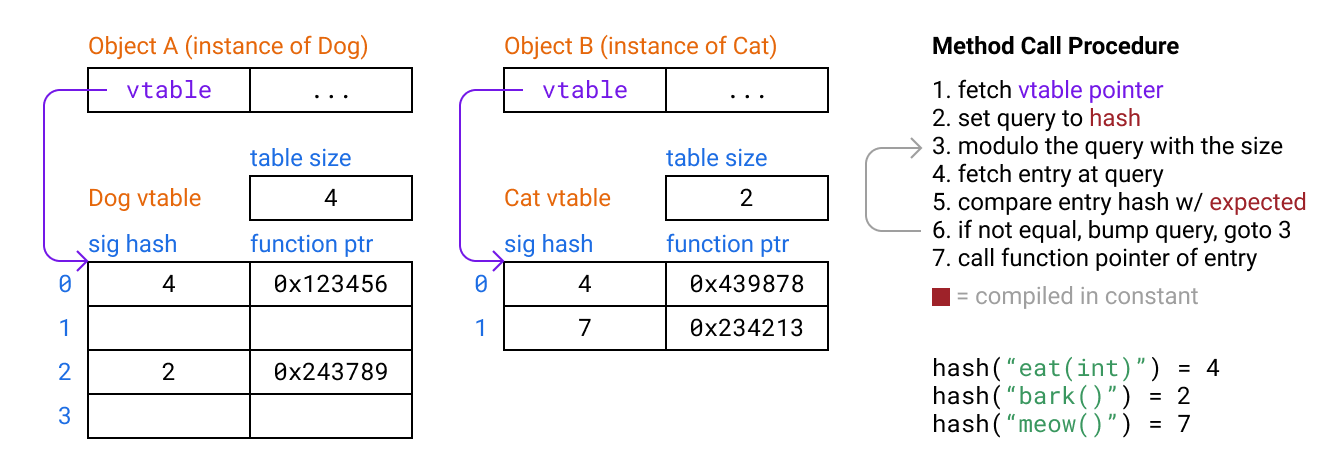

Hashing at compile time

First we’ll take advantage of the fact that we know which signatures are going to be used for each method call lookup at compile time, so we can do the hashing at compile time and then just compare the hashes when probing. This way we don’t even need to store the signatures in table for comparison, just the hashes.

struct TableEntry {

uint32_t hash;

void *fnAddr;

}

void *lookup(TableEntry *table, size_t tableSize, uint32_t queryHash) {

for(;;queryHash++) {

queryHash %= tableSize;

TableEntry entry = table[queryHash];

if(entry.hash == queryHash) {

return entry.fnAddr;

}

}

}

Now our method lookup is simple enough that we can viably translate it to assembly and insert a version of it at every method call site. In the common case of no probing, branch prediction and out of order execution in modern processors should even make it so the cost over a normal vtable lookup is minimal!

Avoiding collisions with rehashing

The above approach has a problem, which is that we stopped handling hash collisions. A method call could resolve incorrectly if two different signatures hash to the same thing. According to my most frequently referenced Wikipedia page, at 32 bits for our hash we’re not safe from collisions in large programs, even if we use a strong hash function.

My solution to this is to keep a table at compile time of which hash value I’m using for each signature. When I’m adding a new signature to the table I append an additional integer before hashing, and if the resulting value collides with an existing hash, then I increment the integer and hash again until I get a value that doesn’t collide. This ensures that comparing signatures only by hash in the lookup is valid because hashes uniquely identify signatures.

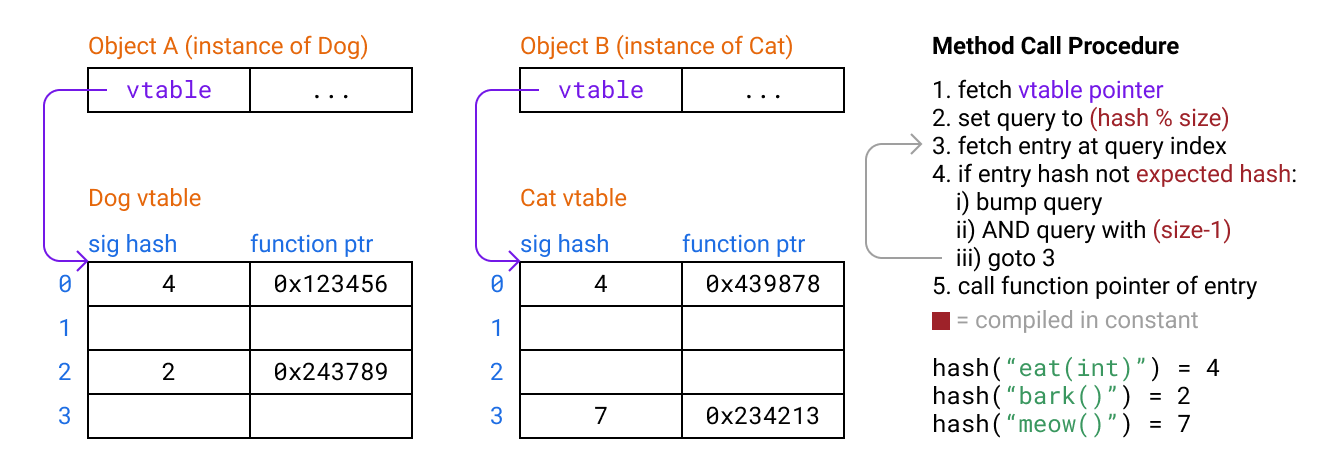

Sizing the table ahead of time

In our above examples we need to pass in the table size to our lookup. If each class can have differently sized tables, we also need to store the size somewhere accessible, like index -1 from the vtable pointer. However loading the size means probably loading another cache line in serial, carrying a performance cost. The solution is to make all our hash vtables the same size.

The other problem is that the modulo operation is relatively expensive, having a latency of 20+ cycles. For the initial lookup we can fix this by also doing the modulo at compile time, then moving the modulo to the probing case of the assembly stub. We can improve the probing case as well by making the table size always a power of 2, and then using a bitwise AND with a constant mask (which has 1 cycle of latency).

In our compiler I computed a fixed power-of-2 table size ahead of time by figuring out how many method signatures the largest table needed to store, multiplying by an arbitrary factor of 4 to avoid collisions (and thus probing), then rounding up to a power of 2. I expect the size of classes follows a power law distribution so the largest class would scale with the log of the size of the program, making total table space O(n log n) in program size.

Probing only when necessary

My final idea was that when I was building the tables I could track which signature hashes ever collide in a table and get placed in a slot other than their home slot, and thus may need probing. Then for all the signatures which never got placed outside their home slot, I could just not generate the probing code at those call sites! Non-probing sites also don’t need to check that the hash is equal (it always will be) and can do the modulo at compile time, making them just indexing a table.

The final probing and non-probing assembly method call stubs look something like this:

; == X86 Assembly for general case with probing, call target in eax

mov eax, [eax] ; eax = address of object -> eax = address of vtable

mov ebx, 61 ; the initial slot index, hash % size

.callcmp:

mov ecx, [eax + ebx*8] ; get the hash at the current slot

cmp ecx, 1062035773 ; check if it matches the expected hash

je .docall: ; jump if it did match

add ebx, 1 ; if not probe to the next bucket

and ebx, 127 ; bit mask for computing i % 128 (the table size)

jmp .callcmp ; check the hash again

.docall:

call [eax + ebx*8 + 4] ; indirect call to the function pointer

; == X86 Assembly for case without probing, call target in eax

mov eax, [eax] ; eax = address of object -> eax = address of vtable

call [eax + 492] ; indirect call to the function at offset (hash%size)*8+4

Our arbitrary max table size expansion factor of 4 lead to only 0.13% of method call sites in our test program corpus needing probing, although larger programs would be less forgiving. This meant that in almost all cases my hash vtables emitted basically the same code as classic vtables would, except that the same vtables also worked for interfaces as well! However the tables being larger than classic vtables in the non-interface case mean they’ll be less efficient with cache space and so would be somewhat slower in practice.

Conclusion

I’ve never heard of anyone implementing interface vtables in this way, but I wouldn’t be surprised if there is prior art because these are all just simple insights you can have by thinking about how to specialize a hash table for this problem. I think LuaJit does some similar tricks for its hash tables where its tracing JIT can specialize on the hash value and optimize an index lookup plus bailing from the trace if the key doesn’t match.

According to my compilers class professor there’s a broad literature of optimizing the “giant table with all signatures” approach with heuristics for saving space by rearranging and merging the tables of different classes into the same space or re-using offsets across classes to make tables smaller. But the general problem is NP-complete so can only be solved heuristically. Interestingly I ended up with a kind of similar direction which re-uses offsets effectively randomly, but then includes a mechanism for handling the resulting collisions.

I hope you found some of these hash table tricks fun and came away inspired to think about how you might be able to modify a common data structure to fit your application better!