Reverse engineering an AI spaceship game at DEF CON CTF

I recently played with Samurai in the DEF CON CTF 2020 finals, and want to write about an incredibly cool challenge I worked on called ropshipai. It involved reverse engineering a binary to discover the architecture and format of a neural network, creating a network to control your spaceship in an arena against all the other teams, then doing a ROP exploit using a buffer overflow to get more capacity for a smarter AI. I hope this article can give you a taste of what high level security CTF contests can be like and why they’re so fun.

Here’s what it looked like near the end of the contest, I cherry-picked a round where our final bot (labeled ‘X’ in light grey) won:

Part 1: Reverse engineering

We were given a download which included a PyGame UI to simulate the game. The UI called out to an x86 binary which we figured out computed the move for a team’s bot using an input file. We figured that file was probably the same thing the “Upload AI” button on the challenge’s web portal accepted. There was a challenge a previous year called “ropship” that involved a similar arena with bots controlled by return-oriented programming and we assumed the “AI” added this year meant a neural net, but didn’t yet see any of the organizers’ usual Tensorflow.

So we started reversing the binary, and my teammates found various functions that seemed to do floating point math and loops, which they started using IDA’s decompiler on and matching up with common neural net functions. They quickly found ReLU, then an iterative function that we figured out produced results matching e^x. We also found a function that at first appeared to be 1/(1-e^(-x)), which was confusing since that’s almost a sigmoid but with subtraction instead of addition. I took a look in Binary Ninja and it looked like addition to me, it turned out IDA had just decompiled it wrong and it was a sigmoid.

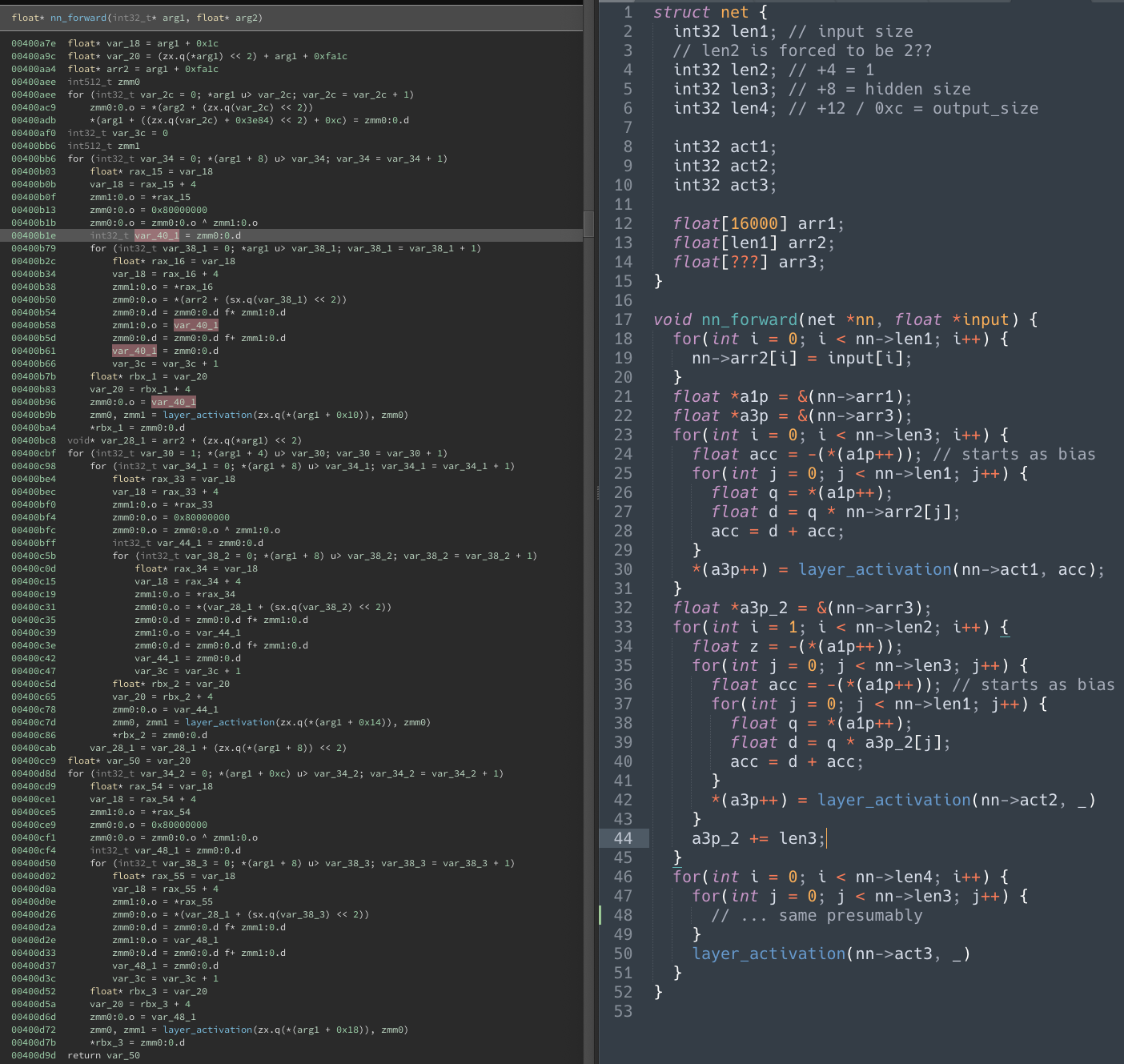

That left the big function with lots of math and loops, which we assumed was the main network evalutation function. I got to work using the new decompiled view in Binary Ninja to try and decipher what it was doing and what the structure of the inputs we had to give it were, while my teammate samczsun figured out the input file parsing code that set up those inputs. At the same time, other teammates figured out the simulator and what inputs it could feed to the network.

I reverse-engineered all the pointer arithmetic and simplified things to write out a pseudo-C version of the network evaluation function. It seemed to evaluate a number of lineary layers with biases, each followed by either a sigmoid or ReLU activation function (chosen by the input file). The input parsing code hard-coding the number of hidden layers between the input and output layer equal to 1, which was weird and fishy.

Once we had collectively figured out how everything fit together, we wanted to get a bot out there and earning points as fast as possible. First aegis wrote a Python network serializer script and deployed a bot that just set the bias on going forward to run us into the wall so we were a smaller target and not in the expected position for anyone managing to shoot. The next bot had hand-designed weights in the matrices to rotate the ship unless it was ready to fire in which case it shot. We weren’t quite the first to upload a non-empty network (an empty file just shot the wall) but we were something like 2nd.

Part 2. Training a better network

While aegis worked on making a smarter hand-coded bot, I started work on training a real neural net to be a better AI. An alternative I brought up was to write something to compile a domain specific language to weights, using the fact I had learned about in my university machine learning course that you could approximate any function using only one hidden layer by using a specific method of engineering weights to set the value of the output for different regions of input. However, given that both aegis and I had done some deep learning training before we figured it would be easier to just use gradient descent.

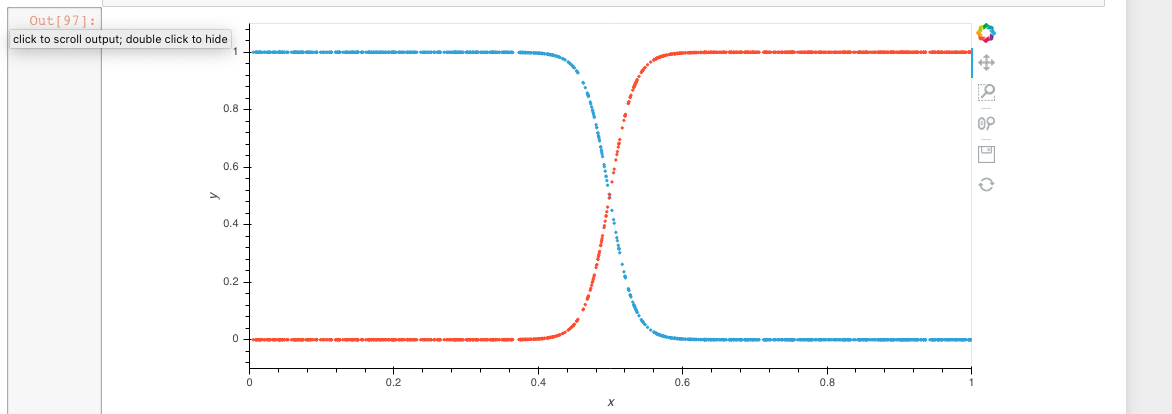

I fired up a Jupyter notebook, replicated the architecture, and thought of a way to make a basic AI by writing a Python function to output what we wanted the AI to do given various inputs, and feeding lots of randomly generated input vectors through the function and training the neural net to match those actions like a normal supervised classifier.

Unfortunately it was harder than I expected and it took annoyingly long tuning hyperparameters and how my training setup worked before I even managed to train a network to do one action if the single input was less than 0.5 and another if it was greater:

Next I worked on modifying aegis’s code, which wrote out his hand-coded weights in the correct format, to take the weights from my trained model. Unfortunately the first network I exported this way just didn’t do anything when run in the simulator. So I spent some time investigating the polarity of how PyTorch did biases, trying out different combinations and reasoning through whether

I wanted to write things out in row-major or column-major order, all to no avail. I even wrote some code to export aegis’s hand-coded weights using my exporter, and that worked but my model still didn’t.

So after around 2 hours I tried using GDB to trace the execution of my model through the binary while referencing the disassembly in Binary Ninja, to see what was going wrong. To my surprise it seemed to exit before it even ran my model, and exited with a weird error code. I bisected it down to find a validation function that limited hidden layer size to a 2x2 matrix, way too small to train anything significant. I posted the bad news in Slack and it turned out samczsun had figured this out a while ago but in the hectic phase of everyone working on different reverse engineering in parallel, the rest of us didn’t hear.

Part 3: The exploiting and fancier bots

It looked like the “rop” in the challenge name wasn’t just a callback to last year’s “ropship” challenge and we’d have to exploit our way into more model capacity. We had already found a buffer overflow on the stack with unbounded user-controlled contents, in the code which fetched the inputs to feed to the network. It seemed like we could craft a ROP exploit to manipulate the size parameters of the network to change them after they had been validated. ROP is a technique where if you can overwrite the address the function call should return to on the stack, you can make it return anywhere you want, allowing you to execute any sequences of suffixes of any functions in the program to perform your exploit. There was a seccomp policy and some weird custom “ASLR” and “sandboxing” that simultaneously made some ROP a bit easier while keeping things contained so we couldn’t easily just break out and exploit the challenge or run arbitrary code as our AI.

I’ve never done ROP so aegis and samczsun started work on that while I patched out the validation in my personal copy of the binary and got to work on training a better bot to work with the eventual exploit. In the mean time chainsaw10 had written some better Python AI functions using a patched simulator to test them out, which I worked on training a model to match. It was again surprisingly difficult. I had a lot of trouble getting it to be able to do actions like shielding, which only needed to happen on around 5% of random inputs. The network would just always output 0.0 for those actions except on some lucky training runs. I suspect something was going wrong with my initialization or gradients such that on most runs the shield output would fall into a place it could never get a gradient signal to recover from.

Three hours later at around 6am I managed to get a basic AI trained which turned towards the closest bot, moved towards it, shot at it and shielded. At that point I went to sleep, the contest had been on a 9 hour pause and I intended to wake up again before it restarted, when the exploit would hopefully be finished.

I ended up sleeping past my alarm until 2 hours after the contest started again. When I woke up, aegis and another teammate had finished the ROP exploit and wrote a converter that added the exploit to the latest bot I trained, and it was deployed and doing decently! The exploit development had hit some snags but eventually landed on something which overwrote the return address to restart the execution of the function with the buffer overflow multiple times to get various things overwritten, to patch in a new network after the hidden size validation had passed on the original overflowing network.

Unfortunately the bot we uploaded was still kind of crappy, it knew how to move around the arena towards a target but it kept doing that until it was right on top of them and then often died if the opponent then shot us at point blank range. It also only used the sine of the angle to the enemy so due to an ambiguity it would sometimes run in the exact opposite direction.

So aegis and I worked on a better training setup with a GPU box and larger networks. In the mean time chainsaw10 had improved the AI function to not get too close to enemies and also be able to dodge bullets. We still had tons of trouble reliably training a network to match the function, but eventually ended up with a slightly better version of our previous bot and a version without very good aim trained on our new bot code. In simulations with our own bots the very accurate but simpler bot did better, so we uploaded that, but an hour later and one hour before the end of the contest I saw it wasn’t actually doing well against the other teams, so I uploaded the more sophisticated bot and it did much better and even managed to win a few rounds. It still had crappy aim and sometimes did the wrong thing though, and it had taken a lot of tweaking to get it to learn to shield.

Postscript: Compiling to neural nets

In hindsight given how much trouble we had training our small neural networks, in what seemed like it should have been a really easy task, it seems like the best approach was to use the universal function approximation proof style tricks to write a compiler from a logic DSL to network weights that exactly implemented the function. I’m still not sure whether we had a hard time training because training shallow networks with small capacity is just hard, or there was some technique we were missing to get our training to work well.

In the last two hours of the contest I worked on a prototype of the compiler approach for fun and managed to get it mostly working. I was using only one hidden layer so my input DSL required providing some constant thresholds on inputs, AND gates on those threshold signals, and then each output was an OR of some of the AND results. This was enough to implement any truth table on thresholds, but it was incredibly wasteful of network capacity to do so and the flattening of the decision tree to a truth table still needed to be done manually. I had some ideas for how to automatically flatten a decision tree Python function into a truth table though using overloaded operators that detected thresholding on the inputs and breadth-first searched to explore the space of outputs, but the contest ended and I wanted to catch up on sleep after that.

I talked to my friend on team PPP, since PPP had a bot with really good clean behavior. He said that PPP did go the route of implementing a compiler to network weights, which could compile an arbitrary decision tree that included vector space arithmetic. They did it without flattening the tree by using multiple hidden layers, which the exploit allowed you to use. Unfortunately while as far as we could tell we should have been able to use multiple hidden layers, when we tried a multi-layer network it failed to do anything, and we never bothered to figure out why, since our training process worked about as well with one hidden layer.

Conclusion

Overall this is the challenge I had the most fun with this DEF CON CTF finals, it combined reverse engineering, neural nets and exploitation, and had different possible valid approaches to solve it. It was super fun to upload an AI and see it dodge bullets and beat other teams based on a tower of hard-won knowledge and code from hours of work reverse engineering and tinkering. In general I get really into DEF CON CTF challenges because they’re a great combination of tractable problems I can work with friends on with fun competitive time pressure, that also are really interesting and difficult to make me feel like I’m exercising all of my available skill.

This was only the last challenge I worked on. Earlier in the contest I worked on rorschach helping aegis by figuring things out and coming up with tweaks to make our black box hill climbing solver exploit a neural net classifier faster, and coming up with defensive checks against other teams’ attacks. In the middle I did miscellaneous reverse engineering and spent hours working on attacks for exploits teams patched before we were done implementing them, and an AI for another multi-team game that closed before I could deploy it. My other AI did have the best dang debugging visualizations a rushed CTF hack has ever seen though thanks to my affinity for HoloViews, which might have had a little to do with why it was too late…