My Text Editor Journey: Vim, Spacemacs, Atom and Sublime Text

I currently use a highly customized Sublime Text 3 as my text editor for almost all programming. However, people are often surprised to learn that I’ve used Vim for 6 months, Emacs/Spacemacs for 10 months (including much elisp hacking) and Atom for a month, yet I still prefer Sublime.

This post explains my journey between text editors, what I learned, what I like and dislike about each of them, and why in the end I’ve chosen Sublime (for now). Most detailed is my reasoning for abandoning Spacemacs, despite being a top contributor and power user, although many of my criticisms of Vim also apply to Spacemacs (and vice versa).

The Early Days: Textmate & Sublime Text 2

My text editor when I first learned programming was Textmate, and I stuck with it for a few years (I forget how many) before I at some point switched to Sublime Text 2’s trial, and then paid for a license.

Back then I only used the basics: syntax highlighting, find/replace, autocomplete, file tree… I didn’t know any keyboard shortcuts besides standard OS ones like copy-paste and undo. I used the mouse for all selection and eventually learned the Sublime command pallete and “open file in project” pallete.

This setup didn’t cause me any trouble, I was productive and nothing was painful. But, I heard tell of the true power one gained upon learning to use a real editor like Vim or Emacs. I watched screencasts where Vim masters would perform impressive editing operations in a couple keystrokes.

Vim: A Taste of Power

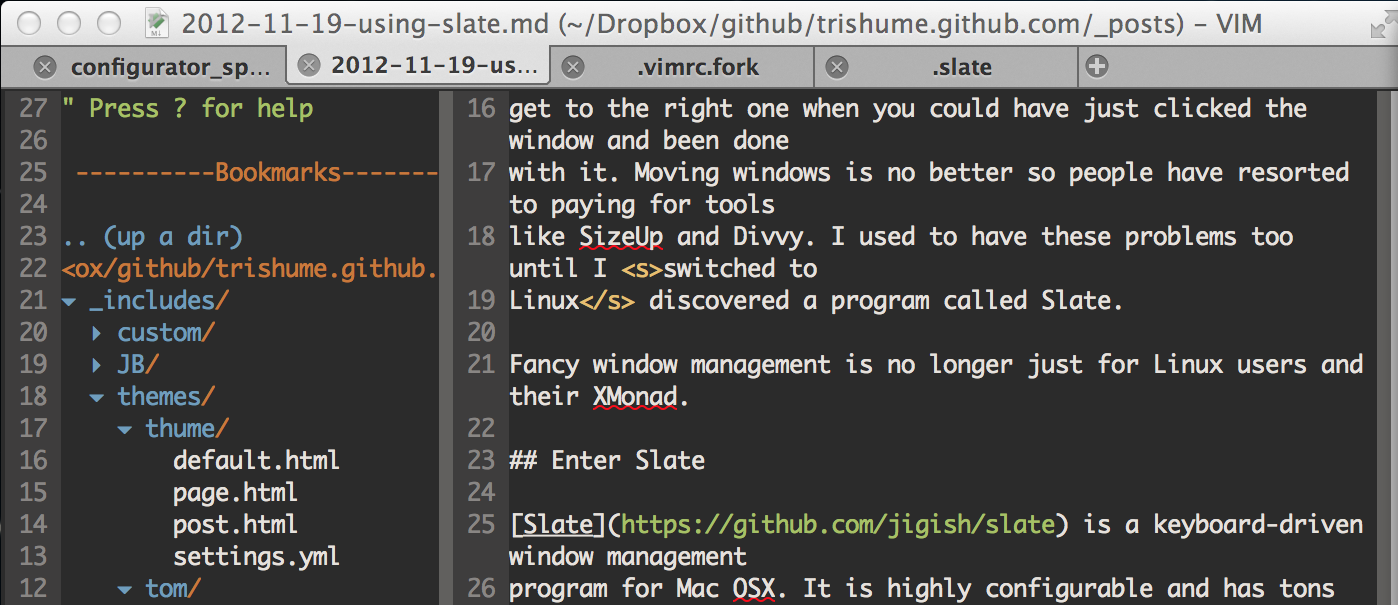

In late 2012 I switched to Vim. I learned the keyboard shortcuts with vimtutor

and printed cheat sheets. I read tons of blog articles (often conflicting) on

learning and using Vim the right way.

I tried using a blank .vimrc and building pieces from scratch making sure I

understood what each piece did each time. However, this was taking far too

long, my editor was missing key functionality from Sublime and Textmate like a

file tree, good autocomplete, open in project, and support for languages I

used. It was also ugly.

So I started using the spf13 Vim distribution. It was nice, and had most of the features I wanted. You can still find my modified spf13-based vimrc here.

I was reasonably happy with this setup and continued using it for over 6 months.

However, there were many pain points. One of these was that things often didn’t work. For example, my tab key was bound to tons of different things like autocomplete, snippet expansion, indentation, moving between snippet fields and inserting the literal tab character. Many of those overrode each other in different contexts, but very often it chose the wrong one. I ended up fixing this somewhat but not completely, but I didn’t have this issue in Sublime because everything was designed to work together so the tab key just always did what I wanted. Even after I fixed it, the hours I spent diagnosing the issue, figuring out how to resolve the conflicts, implementing it, then re-learning my muscle memory probably erased weeks of sub- second Vim speed gains.

Another issue I had was that Vim was mouse-hostile. I was fully aware that the Vim philosophy is to just never use the mouse. However, even with plugins like EasyMotion and ideal vim shortcut use the keyboard is slower for some selection tasks like selecting a range of text far from the cursor than the mouse is. Often using Vim shortcuts felt faster because my brain was engaged figuring out the optimal combination of motions and looking for EasyMotion hints, but whenever I timed myself I was consistently much slower than I was with the mouse. I’m only talking about long range selection and cursor movement here, I totally concede that keyboard shortcuts are better for short range movement and selection. Vim wasn’t that bad for the mouse, but lots of plugins didn’t really work well with it and mouse selection often worked weirdly in some states.

Back to Sublime (with a stint in Atom)

I realized that I didn’t like fighting my editor and loved the ease of use and mouse support of Sublime. However, I also loved the power of Vim’s keyboard model. Luckily, I could use Vintageous.

This way I could get all the power I liked about Vim with all the niceties of Sublime.

In fact, Vintageous is arguably more powerful than Vim itself because it works with multiple cursors. Using multiple cursors with Vim bindings is incredible, it’s basically the same power as Vim macros give you, except you can compose them on the fly with instant feedback about what commands did at each place you wanted to use them (see gif below). I found I rarely used macros with Vim because I had to think hard about which commands I could use that would work on every instance and make sure I didn’t screw anything up, then figure out how I wanted to run the macro for each location, but with Sublime it was so easy I did it all the time. Yes, I know both Vim and Emacs have multiple cursor plugins, but they are hacks and don’t seamlessly work with all commands and together with the mouse.

I started using Sublime as a power user’s text editor just like I had used Vim. I learned the keyboard shortcuts, read about the functionality and installed plugins.

For a month I also tried out Atom. I pretty much replicated my Sublime Text setup with the equivalent Atom plugins, plus some extras that only Atom offered. However, I preferred Sublime’s speed. It wasn’t just that some editing operations had a bit of latency, but that Sublime could offer features that Atom couldn’t because of its speed. For example Sublime’s “open in project” panel instantly previews the files as you type because it can load files in milliseconds, and search is incremental by default.

I used this setup quite happily from mid-2013 to late-2014. However, I started

thinking about the possibility of using Emacs with evil-mode. I’d heard its

Vim emulation was fantastic and the possibility of using Emacs lisp to craft

the perfect text editing experience given time was enticing.

I started looking around at various Emacs starter kits like Prelude and tried out a few. I read Emacs articles, documentation and blog posts about people’s Emacs configs. However, everything had really horrible convoluted hard to remember keyboard shortcuts that didn’t fit well with Vim’s.

Spacemacs

Then, I found Spacemacs. It was exactly what I was looking for. It was pretty, integrated Vim and Emacs functionality in an interesting and discoverable way, and promised to have everything set up to work out of the box. Somehow this project only had around 12 stars on Github and no other contributors. It seemed the creator had poured tons of effort into making a fantastic project, but unlike most people’s dotfiles, he put effort and thought into making it adaptable to individual needs and documenting how to do so. I was stunned that this project only had ~20 stars and no other contributors.

So I downloaded it, started working on my own .spacemacs file and joined the

Gitter chat the creator had set up. A little while later I submitted the first

contribution to the project.

Little did I know at that point that the reason it only had 20 stars was that by chance and lots of Googling I had just stumbled upon it earlier than everyone else. Over the coming weeks I continued tweaking and sending PRs and other early adopters like Diego trickled in to the chat and started contributing.

As I used Spacemacs I often noticed things that worked poorly or not at all. I kept steadily fixing most problems I found and adding new contribution layers for the things I wanted. When I was using Spacemacs for something where I had already fixed most of the bugs, it was quite nice and felt efficient.

I continued using Spacemacs for around 6 months and maintained my position as top contributor for most of that time. I helped newbies out in the Gitter chat, triaged PRs and contributed and maintained a few different layers.

I thouroughly enjoyed contributing to Spacemacs, but nearly everything I contributed was fixing a bug or annoyance I encountered while trying to get something done, often writing the elisp to fix an earlier problem.

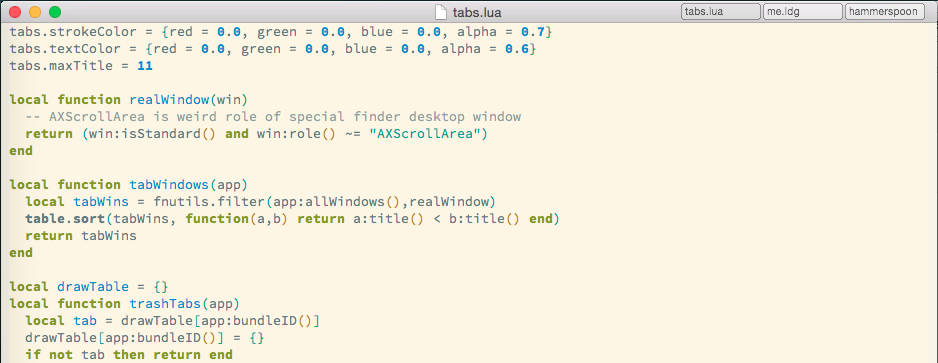

Brokenness

These yak-shaving tasks ranged from fixing annoying keybinding conflicts that Sublime Text had built-in logic for, to getting LaTeX support to work. I even wrote a general mechanism for tabbing OSX windows to get around how bad all the Emacs tab/workspace plugins were. I definitely noticed my annoyance but I ignored it since I was having fun and I had hope that things would get better after more work.

However, after six months of making almost no progress on other projects while discovering and fixing bugs and implementing things I missed from other editors, I realized that there might not be an end. Part of the problem is that I love learning new languages and doing different kinds of projects. Other Spacemacs users might make a few fixes here and there for their primary use case, whereas I was stuck adding support for D, Racket, Nim and Rust and then fixing the bugs I exposed when changing my workflow.

I think the underlying reason is that everything in Emacs, and especially Spacemacs, is a hack. Core Emacs offers almost nothing and everything is layered on top as ad-hoc Emacs Lisp additions. Different third-party plugins and to some extent base functionality step on each others toes and make conflicting assumptions all the time. One particularly bad example I ran into is my Emacs hanging mysteriously when autocompleting on some two character suffixes. After much searching it turned out to be a known issue where if what I was completing looked like a domain name Emacs would try to ping it because of an interaction between autocompletion, file finding, and remote server support.

Lack of Consistency and Discoverability

Another problem with this pile-of-hacks design is that nothing was consistent or discoverable. Every moment I saved on common operations due to efficient keyboard shortcuts was cancelled out by a minute spent searching for how to do a less common operation that I didn’t do often enough to memorize.

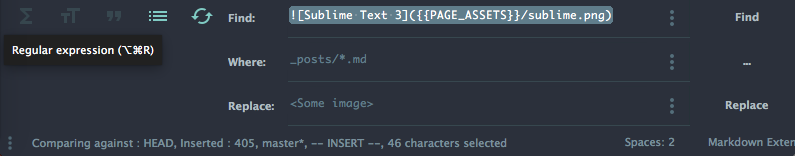

An example of an occasional workflow I can do in Sublime is:

- Paste my clipboard into the search box.

- Search all files in a project for without regex support (useful when searching for a string with special characters that you don’t want to escape), case insensitively.

- Narrow it down to a glob of certain files without re-typing my query.

- Edit my query slightly to refine the results, again without re-typing it.

- Replace the content of all those occurences once satisfied.

I tried to do this in Emacs once, and had to spend a ton of Googling and investigating M-x listings:

- Look up how to search in project without regex (I’ve never figured out a way to do this)

- Look up the shortcut for pasting into the minibuffer (I use Evil so I can’t use

plike usual). - Hope that the command is Helm-based so I can edit my query, otherwise re-type everything to narrow it down.

- Look up how to replace in project without regex, oops it’s an entirely different command from searching.

- Re-enter everything into the new command and run it.

Navigating Multiple Files

The last major problem I had was how difficult it was to work with code spread across multiple files compared to Sublime Text.

There’s three main ways for working with files in Emacs: buffers, files and windows.

I tried using buffers but the problem is that buffer switching is slow and difficult. It only takes one keystroke to switch to the most recently opened other buffer, if you remember which that is, but switching to other buffers requires waiting for a list to show, reading it, then multiple additional keys to select the right one. Buffers also tend to proliferate like mad and these lists end up enormous taking many keys to filter to the right one. They are also nearly impossible to navigate with the mouse if I’m reading code and that’s where my hand is.

Navigating using normal find-file and helm mechanics has a similar problem:

switching is just slow. It takes a lot of key strokes, and those strokes sometimes

involve waiting for a list to appear that you can read.

Having your frame/screen split into a bunch of windows (Emacs reverses the

meaning of window and frame from every other editor) in Spacemacs has the

advantage that each window has a number on it and you can hit SPC+1 to

SPC+9 to switch directly to them. This is great in that it is very fast and

easy to remember, find and see where you want to go and how to get there. The

problem is that you sacrifice screen real estate for every new file you work

with. I normally ameliorate this with golden-ratio

mode, which shrinks unfocused windows, but they still take up space.

With Sublime Text I use tabs, which are amazing. I can switch quickly and directly

between files with cmd+1 to cmd+9, see all the files I’m working with at a glance,

and navigate with the mouse if I want to. I can also easily rearrange tabs so that the

most frequently used and important files are on lower consistent numbers that I can subitize.

I can even use ZenTabs to ensure that I only

ever have my 9 most recently used files open in tabs, eliminating buffer proliferation.

Infrequent but useful actions like moving a file between windows and panes, and copying the file

path are all obvious discoverable mouse actions. The file I’m working on always fills the full screen,

unless I want to reference other code in another pane. When the file I want isn’t a tab

I can open it with “Goto Anything”, which is similar in speed to narrowing to a buffer by name.

When I want to navigate based on a project’s directory structure I have access to a fantastic

file tree.

Yes, Emacs has plugins to add tabs but they are hacks. They’re ugly, slow, break when used with other plugins, don’t have good keyboard shortcuts, and display tons of useless buffers I don’t care about.

When I watch friends and coworkers use Vim and Emacs this is the thing I notice most. They look super efficient since they’re furiously typing things or navigating directories, but often the file they are opening is one that they looked at just a minute ago and would have taken me a single keystroke to switch to. They however have to type a bunch of characters to narrow to the buffer name. I even frequently see Vim/Emacs users opening files by navigating directories when I would have just typed a few characters into “Goto Anything”. Emacs and Vim also have ways to fuzzy search for a file in a project, but the heuristics and tools are often so bad and slow that they give up and fall back on manually finding the file. I’ve never seen a Vim or Emacs users who navigates between files as fast as I do in Sublime.

Realization

I realized that despite all my work and the work of other contributors using Emacs was still a pain and I longed for the just-works nature of Sublime Text. It didn’t help that many operations in Spacemacs had surprisingly high latency (similar to Atom) and many things were ugly (like the file tree). I said my goodbyes to the Spacemacs community and headed back to Sublime Text.

I still think Spacemacs is overall quite good though. If you’re someone who mainly codes in one language, especially a popular one, then you can get Spacemacs set up to do exactly what you want, and the huge community nowadays means that either the bugs will have been fixed or you can easily get help with the ones you encounter. I’ve listed a bunch of disadvantages, but Emacs has powerful features that Sublime doesn’t, I just didn’t like what I had to give up to get them.

Sublime Text 3: Back With Vengeance

So I switched back to Sublime Text 3, but just like after Vim, I took some of the things I enjoyed back with me. I updated my plugin and keybinding arsenal to include many of the handy things I used in Spacemacs.

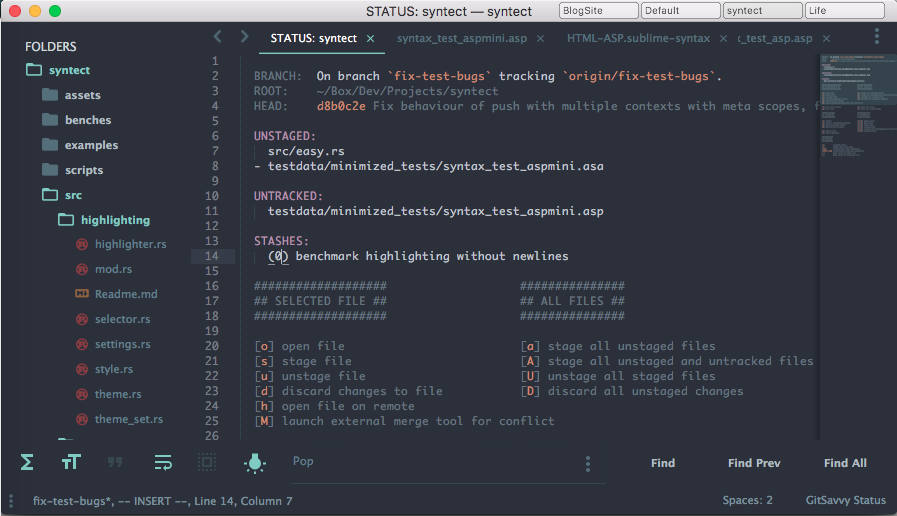

One thing I really enjoyed in Emacs was Magit, so I installed GitSavvy in Sublime and found it had almost everything I liked about Magit. I even like its workflow marginally better and the Github integration is top notch.

I set up the Alfred Git Repos workflow to replicate opening projects with Projectile, and used my OSX window tabbing plugin to manage my Sublime Windows as well.

The fanciest thing I did was create my own set of keybindings that work like Vim except with the palm keys of my custom keyboard as the mode. That way it is faster to quickly do movement and editing actions in the middle of writing. It also synergizes way better with the mouse because I never am in an unexpected mode when I use it and then move back to the keyboard since they physical state of my hands is the state of the editor. I still drop into Vintageous mode for fancier editing though.

And all this took me only a few evenings to get to a point where I was happier with it than the Spacemacs setup that had taken me six months. I’ve been using this setup happily since mid-2015 with only a couple bugs which were quickly fixed, despite using the dev builds of ST3 and many plugins it’s been orders of magnitude more reliable than Emacs.

Jane Street

Then I went to work at Jane Street for an internship and ended up migrating back to Spacemacs for a little while. Jane Street has a bunch of internal Emacs tooling, and even a bunch of custom integration with Spacemacs, along with much more mature tooling for OCaml than Sublime Text.

It was mostly pretty good, but far from smooth sailing. Various internal and external Emacs plugins I used conflicted on their idea of where windows should go and took over other windows, almost actively replacing whichever window I cared about most. I encountered tons of bugs, both large and small. Many of these I ended up patching myself, either with dotfile snippets or pull requests.

Not only did I encounter over 20 different Emacs, Spacemacs and plugin bugs

(some annoying me quite regularly) during my four months, but there were other

problems. Jane Street’s massive code base made many plugins slow to a crawl.

Synchronous autocompletion with Merlin occasionally hung Emacs. Using helm-projectile

was unbearable without caching and slow even with it. Until I disabled a bunch

of hooks saving files took seconds due to hg commands running slowly on the large repo.

Eventually I talked to the one guy using Sublime Text at Jane Street and got his set of plugins and settings for working on Jane Street’s OCaml with Sublime. I modied the Sublime Merlin plugin to support tooltips that showed the inferred type of an expression and clickable links to the file of definition and declaration.

I then started using Sublime Text for sprees of reading code, but not for writing it. Sublime still had far worse support for building and indenting Jane Street code. But, this way I could understand things faster by using quick fuzzy search of files, excellent tabs, smooth scrolling with the mouse, and tooltip links to navigate the codebase.

Eventually I started using Sublime for editing as well, after I improved indenting, highlighting and autocompletion slightly. I still kept Emacs open to run the source control, code review and Jenga build plugins, but I set up elisp so that it navigated to compile errors in both Sublime Text and Emacs. This offered an excellent compromise between nice plugins and a good editor that I was happy with.

Despite all the additional functionality and improvements I made to Sublime, I actually think I spent less time on getting Sublime to work than on fixing, debugging and setting up Spacemacs while I was there.

Closing Thoughts

Overall, I’m still very satisfied with Sublime Text. I think text editors could go a lot further than they are now, but so could most software. I feel very productive, I never fight my editor, and it works for any language I throw at it.

I would love it if Sublime was open source, or if there was an open source editor that was as good. However, I realize that many of the reasons I love Sublime wouldn’t be possible without it making money. The reason the creator(s) can pour so much effort and care into every detail is that Jon (and now also Will) can work on it full time for years. No other text editor has a custom cross-platform UI toolkit, a custom parallel regex engine, and incredibly fast indexing, search and editing engines.

I also realize that in some respects Sublime’s rather limited plugin API is an advantage. Unlike Emacs/Vim/Atom I rarely have to worry about plugins slowing down my experience by accidentally doing something synchronously on the entire file, since the API almost enforces asynchronous design. No plugin can break core functionality or slow startup times. Plugins are forced to work only in ways where it is difficult to conflict with each other since two plugins can’t implement hacks in the internals that interfere with each other. When Emacs plugins implement “helpful” hacks to basic functionality that conflict and break things, my approach is often to disable them since I rarely want these hacks anyway.

Sublime can also get faster and better every release because they don’t have to worry as much about piles of hacks restricting how they can change their internals. Like how Atom constantly has to deprecate old APIs whenever they restructure to improve performance.

Also, the recent dev builds have patched what I think was the number one hole in Sublime’s plugin API: tooltips and inline annotations. Now plugins can implement fancy custom tooltips with links and colours and formatting using a subset of HTML. This same HTML subset can also be used to inject “phantoms”: rich text annotations of code for things like previewing LaTeX formulae, colours, types, lints and errors. This should allow most of the useful plugins that previously were only possible in Atom/Emacs to be ported to Sublime, but since it is implemented centrally instead of a bunch of different ways it will work seamlessly and consistently.

I’m optimistic for the future of Sublime Text. I’d love to see a new editor that’s open source and as fast, nice and powerful as Sublime, but I don’t expect to since it would be a ton of work. Visual Studio Code looks pretty awesome though, if I was writing Javascript I’d consider it for the excellent tooling integration, but for less common languages it doesn’t look any better than Sublime.

I wrote this post because I often find myself justifying my use of Sublime Text to Vim and Emacs users. They often look at Sublime users as people who just haven’t put in the effort to learn a real power user’s text editor. They’re confused when they learn that I have tried Vim and Emacs extensively and still choose to use what they see as a basic newbie editor. I hope this post explains why Sublime is an excellent choice for a highly customizable power user’s text editor.

Edit: FAQ

Some responses to questions I’ve seen raised after posting this:

You just haven’t learned Vim. A real Vim user could do long distance text selection faster.

I think I know vim quite well, I’ve been using vim bindings for 5 years now across varying editors. I know almost all Vim bindings.

How about a test? Suppose my cursor is on line 198 of this file I want to copy match_pat.has_captures && cur_level.captures.is_some() on line 172. If you give me an efficient sequence of vim bindings for that movement I can tell you if I know what everything does without looking it up.

I think a more apt criticism would be that I think too slowly to use Vim. I can figure out that “26j4wy10e” does what I want, and at my normal english characters/second typing speed that is faster than doing the selection with my mouse. However, when I actually try and do that without figuring it out ahead of time I take longer to read, count and figure out the right numbers and actions, then type the individual characters (which due to muscle memory for english I’m slower at than typing english). I end up being slower than the mouse, and with a higher mental load.

You could say I just need to “git gud” and practice, but if practicing for hours a day for 5 years doesn’t get me to the point that I’m better than the mouse, I think it’s time to say that maybe it isn’t a lack of practice. More likely it’s an innate skill difference, processing speed, counting, typing coordination, or a combination of the above. I do actually use Vim bindings a lot of the time, I know them well, and I know when it is faster for me to use the mouse.

That all presumes that there exists a substantial number of people who are faster in practice at long distance text selection with vim shortcuts than I am with the mouse. I have yet to see someone where I can confidently say that is the case, and I’ve watched a reasonable number of vim users. Some are within the margin of error where I would have to do a timed race with a stopwatch, but I haven’t seen any that are clearly meaningfully faster. I guess everyone I’ve seen using vim (including many 5+ year users) could be a “vim n00b”, but that sounds a bit “no true scotsman”-like.

If you used stock Emacs without all the bloat it would be faster and stable.

Yes it would have been faster and more stable, however then I would just complain about the lack of a bunch of features from Sublime that I like, and the terrible keybindings.

I also have minor RSI issues, I’m not keen to turn them into major RSI issues by using Emacs bindings.

You can only switch directly to a few tabs, buffer switching is logarithmic time for many buffers.

Yes, but tabs are more like a cache. Like I mention, when it isn’t easy to hit the numbered shortcut to jump directly to a tab I use “Goto Anything” to narrow directly to the file, which takes the same amount of time buffer switching would.

Tabs are just an additional speedup in the case that I’m switching to one of my ~6 most recently/frequently used files. I’d say it’s the case that over 95% of my switches are to one of my tabs, but only at most 50% of my switches are to my most recently used other file, there’s gains to be had over Emacs in that extra 45% of switches that become fast.